As Australia prepares to lift the ban on international travel, the federal government has awarded Irish-based IT multinational Accenture a A$75 million contract to develop a Digital Passenger Declaration (DPD) system.

These new digital passes, announced this week, will replace two current documents: the physical incoming passenger cards filled in by all international arrivals to Australia, and the online COVID-19 Australian Travel Declaration, which details travellers’ COVID vaccination status.

With international travel restrictions set to be lifted for vaccinated Australians once the nation reaches 80% vaccination, it is not yet clear whether unvaccinated foreign travellers will be allowed into Australia once the international border opens, or whether unvaccinated Australians will be allowed to travel overseas and return.

It is also not yet clear how the new system will interact with the COVID “vaccine passports” the government has pledged to make available to Australians from next month, allowing them to prove their vaccination status using either a digital or printed document.

The federal government says the new DPD system will also be able to share details of international travellers’ health and vaccination status with state and territory health authorities.

And Stuart Robert, the federal minister responsible for digital data policy, said the program could be extended in future to cover visas, import permits, licences, registrations and other government-issued documents.

While many of the details remain to be confirmed, the announcement prompts a range of questions about how the new digital passenger declarations will work in practice.

Is the new document a ‘vaccine passport’?

Travellers arriving in Australia, both Australian and foreign nationals, have previously been required to fill in a physical declaration card.

Travellers arriving in Australia, both Australian and foreign nationals, have previously been required to fill in a physical declaration card.

Not really — it’s more than that, because it also replaces the yellow arrival cards that will be familiar to anyone who has travelled to Australia on an international flight in recent years.

Besides this, the system will also allow passengers to digitally upload their COVID vaccination certificate. It’s not yet clear whether this will be the same document as the “vaccine passports” set to be issued by the federal government from next month.

The vaccine passports can be shown to immigration officials in other countries, whereas the information in the DPD is purely for collection by Australian officials. It’s also not clear what documents foreign arrivals will be able to use to declare their COVID vaccination status to Australian authorities via the DPD system.

Read more: Vaccine passports are coming to Australia. How will they work and what will you need them for?

How will privacy and security concerns be addressed?

Arriving travellers completing an incoming passenger card disclose lots of personal information, such as their full name, passport number, intended address in Australia, and declarations relating to customs and quarantine.

The new proposed DPD system will capture all these details, as well as the traveller’s COVID vaccination status. This raises several questions about how these data will be collected, transmitted, stored, accessed and shared.

A digital-based system comes with increased cybersecurity risks, and cyber criminals will doubtless be on the lookout for any vulnerability. There will also need to be clear policies detailing which federal, state and territory agencies are granted access to the data.

Will it be mandatory for overseas arrivals to declare their vaccination status, and will they be refused entry if they can’t prove they have been vaccinated? We don’t know yet.

Will authorities determine who needs to quarantine based on their vaccination status? Will Australia implement a traffic-light system, similar to other nations such as the United Kingdom, to identify which countries pose their biggest risk from unvaccinated travellers?

It is also unclear whether the system will be offered in languages besides English, and whether alternatives will be provided to those with accessibility needs or who lack access to a digital device.

How will travellers’ vaccination status be verified?

Recently, federal trade minister Dan Tehan told ABC radio the government is working with the International Civil Aviation Organisation on a QR-based system that would allow Australian vaccine certificates to be internationally recognised.

However, it is unclear at this stage whether the new DPD system will use the same system to verify the vaccination status of Australians returning home, and whether it will be able to verify foreign travellers’ vaccination status without further checks.

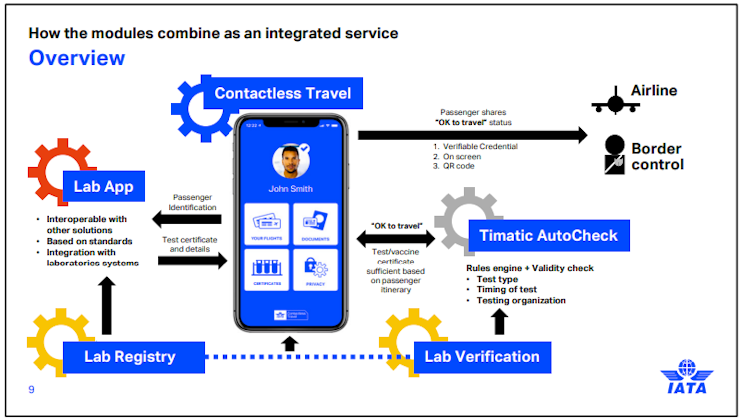

At the same time, Qantas is investigating ways to integrate yet another system, the IATA Travel Pass, into its own app. This system, developed by the International Air Transport Association and already used by airlines in several countries, allows passengers to securely store and present their COVID vaccination certificate, and to find information on testing and vaccine requirements for their journey.

IATA Travel Pass.

IATA

IATA Travel Pass.

IATA

Why isn’t there a globally unified approach?

European Union residents can already use the EU Digital COVID Certificate app to travel freely between member nations, and to other participating countries such as Norway. The app uses a QR code signed with a digital signature to ensure authenticity without needing to collect extra personal details from the holder.

EU Digital Certificate app.

EU Digital Certificate app.

New York state, meanwhile, has adopted a blockchain-based app called Excelsior Pass, which provides digital proof of COVID vaccination or negative test results. It works by searching the state’s health department records, using special cryptographic signatures to ensure COVID certificates and health data are genuine.

For the time being at least, international passengers will likely need to use several different apps to prove their vaccination status in various parts of the world. There are obvious issues with this beyond simple inconvenience, such as data and privacy protection.

Will the system discriminate unfairly?

My research shows that the absence of a unified approach to COVID-19 contact-tracing apps was the main driver behind their failures worldwide. Similar problems are now arising with the rapid proliferation of national and international COVID certificates, travel passes and vaccine passports.

One issue is compatibility. The Excelsior Pass app, for instance, only works on devices running Apple iOS version 13 or later, or Android version 7 or later.

But more importantly, people should have the right to prove their vaccination status without needing to carry a smart phone. Even in a rich country like Australia, only about 80% of the population owns a smart phone, and the rate is lower in developing nations. A system that relies solely on apps would disproportionately deny freedom of movement to poorer people.

Other issues go beyond the choice of technology involved. Legislation will be needed to ensure people with a valid reason for not having been vaccinated do not face discrimination as Australia and the world gradually open up their borders.

Authors: Mahmoud Elkhodr, Lecturer in Information and Communication Technologies, CQUniversity Australia